Coding for the Future

BY STEPHANIE HAMMON

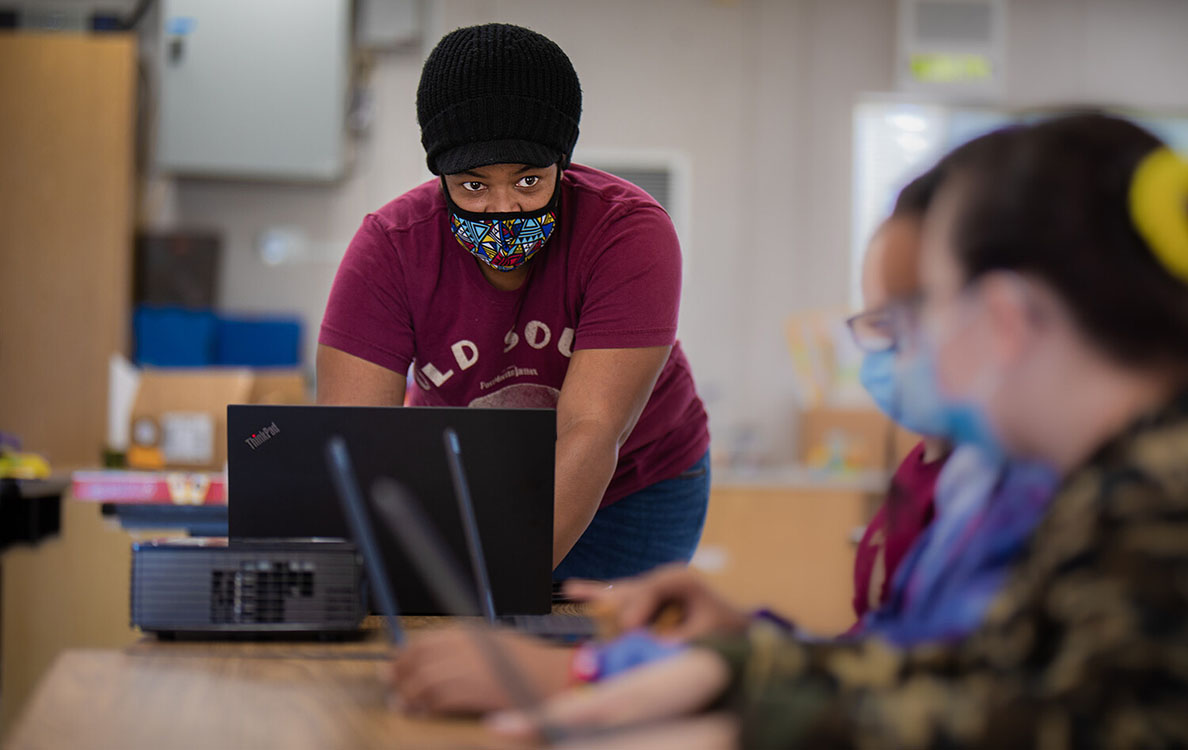

PHOTOGRAPHY BY GARVIN TSO

October 27, 2021

Jeni Williams has never worked in tech, but she has a lifelong interest in computers and believes they’ll continue to play a powerful role in the lives of younger generations.

The school where she teaches, Glassbrook Elementary in Hayward Unified School District, is about 30 miles from Silicon Valley. The region is home to some of the most innovative tech companies in the world, yet many kids at the Tennyson neighborhood school less than an hour away don’t have regular access to technology at home — and little exposure to what it can do.

“Coding is really going to be the language of the future and it’s important for kids to see it as early as possible.”

“Coding is really going to be the language of the future and it’s important for kids to see it as early as possible,” said Williams (M.S.’21, Special Education, Mild/Moderate Support).

It’s what led her to spearhead the Glassbrook Coding Club.

Today, Williams opens her classroom at lunchtime and after school, welcoming students of various grade levels, backgrounds and abilities to learn the basics of coding and computer programming. She started the coding club in 2019. It was first open to the students in her special education program, but when word quickly spread about how much fun they were having, Williams opened the club to other students at Glassbrook.

“Pretty much the minute I tell them they can build games with it, they’re on board,” she said. “I sell them on the gaming part and they stick with me through the basics part. It teaches problem solving, it teaches logical thinking. It can teach math, it can teach dialogue — just so many different things — and it’s a different way [of learning] that doesn’t feel like a class.”

Williams has always had a passion for education, but it took her a while to find teaching as a profession after earning her undergraduate degree from Stanford. Her circuitous career path eventually led her to a role as an after-school program coordinator, where Williams realized that to make the difference she wanted in kids’ lives, she needed to be a classroom teacher as well.

She enrolled in Cal State East Bay’s teaching credential program and initially planned to substitute teach while going to school. However, it turned out that Glassbrook needed a resource specialist for students with mild/moderate disabilities, and the school’s administration gave Williams the job, thanks in part to her extensive tutoring background.

One of her favorite stories to tell about the club’s impact is that of a sixth grader who struggled with reading and was learning English as a second language.

“She picked up coding really fast because the coding we used wasn’t reliant on language. She could rely on colors and knowing the first few letters,” Williams said. “So a kid who had trouble reading books at all, of any level, was able to become a leader in the coding club. That really is my inspiration.”

Making coding accessible to kids of all ability levels is the subject of Williams’ recently completed master’s project at Cal State East Bay, where she volunteered her time at Pioneer Pals, a virtual summer camp hosted by the Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences department. There she introduced kids on the autism spectrum to coding, too.

“The hope is that they are exposed to a skill they aren’t being taught in school and that it clicks with them and opens future doors,” said Shubha Kashinath, the camp’s director and chair of Cal State East Bay’s SLHS department. “These are smart kids, they just learn differently.”

Now in her fourth year at Glassbrook, Williams is thrilled to be teaching her students in person again. The district went almost exclusively online for the first 18 months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Glassbrook Coding Club will be returning as well, giving these young students early exposure to what could eventually be a steady and lucrative career path. For Williams, that’s a huge part of what education should be.

“I think we really need to look at shifting education away from just being about learning for a test or learning specific content,” she said. “And to focus more on what is going to get students jobs when they graduate from high school.”

PROJECT ASPIRE

Funded by a grant from the Department of Education, Cal State East Bay’s Project ASPIRE provides funding for 16 master’s degree candidates each year to receive additional training and experience working with people with autism. The program emphasizes a holistic training approach aimed at offering a better understanding of the lived experience of students on the spectrum whom professionals will be supporting.

Williams’ education at CSUEB included being part of Project ASPIRE’S inaugural year of programming.

“It really helped me see the students’ challenges in a way where I could actually help them make progress,” Williams said. “It gave me a richer understanding of the students I’m working with but also how to help their parents and caregivers … It’s made me a better teacher already and I know it will continue to.”

Share this story