Researching and Embracing Indigenous Tradition

BY Elias Barboza

June 7, 2022

A new project is baking at Cal State East Bay, and students and staff are fired up for it.

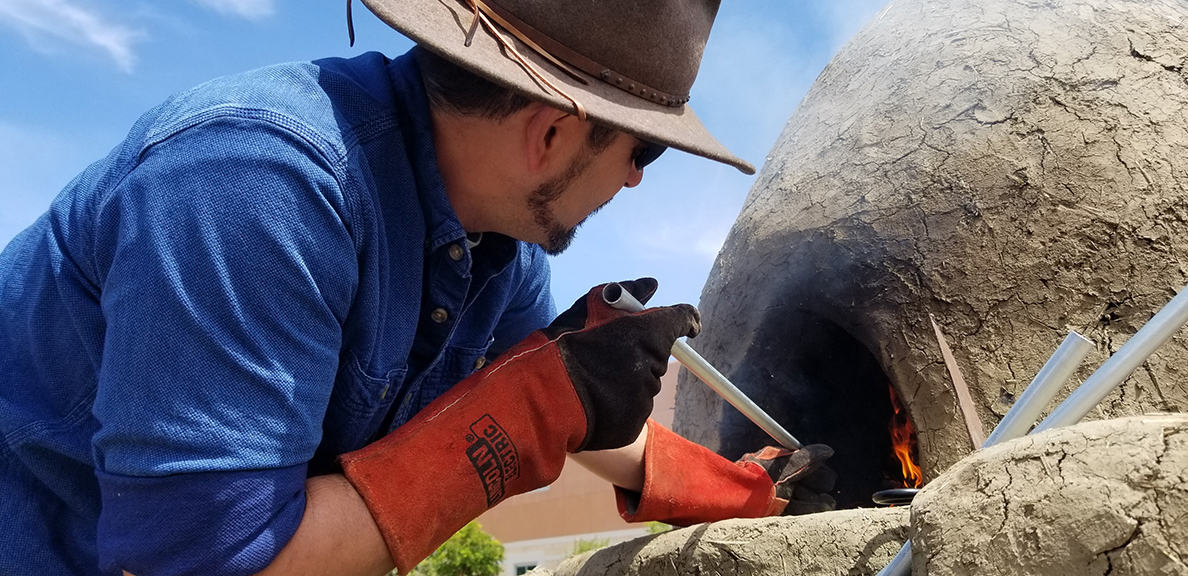

Cal State East Bay and the University of California, Berkeley recently collaborated to build an authentic adobe horno on CSUEB's Concord campus. An “horno” is an oven made of mud and straw, known as “adobe”, that was used by early Native American settlers in North America.

The Tres Hornos Project will help anthropology and archaeology students learn about ancient cooking techniques, as well as help identify other hornos and similar structures in future ancient sites.

“Our goal with this project is to do all the science behind it, but also to build community,” said Jun Sunseri, project lead and associate professor of anthropology at UC Berkeley. “There were Cal [Berkeley] and CSUEB students, faculty, staff and family members involved, getting their hands dirty and working together. It’s fun to bake stuff too. I’m excited to experiment with this technology that's pretty old.”

Prior to the Concord horno, Sunseri’s team built two other hornos on top of concrete in a confined space in Berkeley. Concord’s horno is the first to lay on actual soil, with natural, ample space. After several baking sessions, the horno will be demolished and the remaining soil underneath and around it will be studied. The horno has already been put to the test a few times, successfully baking cookies and pizza.

Instruments were used to scan the area before Concord’s horno was constructed. The same instruments will be used to compare the surroundings after the horno’s use. Sunseri hypothesizes the weight and heat released from the horno will have significant results.

“This study gives us a better idea of the kind of community that lived in a specific area,” said Sunseri. “Traces of the types of food that were baked could be trapped in the bricks that make up the horno. Certain crop grasses and pollen would also be integrated into the adobe, so we could, technically, take a sample of the adobe and use it as a paleoethnobotanical record of a site.”

The horno project began when Sunseri developed a friendship and teamed up with CSUEB Associate Professor of Anthropology Albert Gonzalez. At the Concord campus, Gonzalez facilitated the project with administrators and planned out the construction site. He and a family member helped build the Concord horno with a handful of students and staff.

“I work with adobe because of the feeling I get when I'm mixing mud or laying bricks with people I know and care for, whether it's one person or a hundred,” said Gonzalez. “My father-in-law and I did the final plastering for the Concord horno and we had a great day of bonding and storytelling. Adobe facilitates that kind of connection, encourages it, even. In the old days, and in many places still today, adobe helps to build communities.”

The Tres Hornos team has taken advantage of this project by experimenting with mixing and molding bricks for more effective cooking, and also testing different ways to make them stronger. These techniques will lead to sturdier future hornos.

Morino Baca, a UC Berkeley master’s student of public health, plans on staying involved in those future projects. He’s played a significant role in sourcing the materials to make the horno as well as assisting in mixing the adobe. According to Baca, the most important aspect of the horno project is keeping indigenous traditions alive for generations to come.

“This is more than just an oven,” said Baca. “It’s the labor, the mixing of the adobe, collecting the wood, making the bricks, building the horno, making the fire, going out and getting the food, and — most importantly — coming together. This is indigenous knowledge passed from elders to youth. Hornos are a place where we come together and feast and stories are told. Opportunities like this help these traditions stay alive.”

An authentic adobe horno on the Concord campus is providing hands-on learning for anthropology and archaeology students.

Share this story